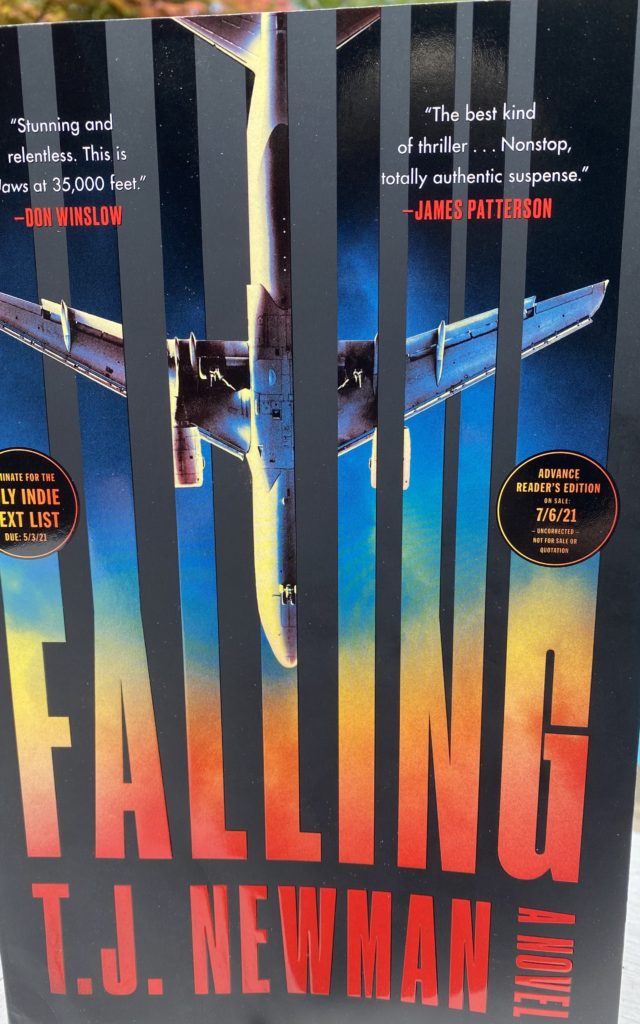

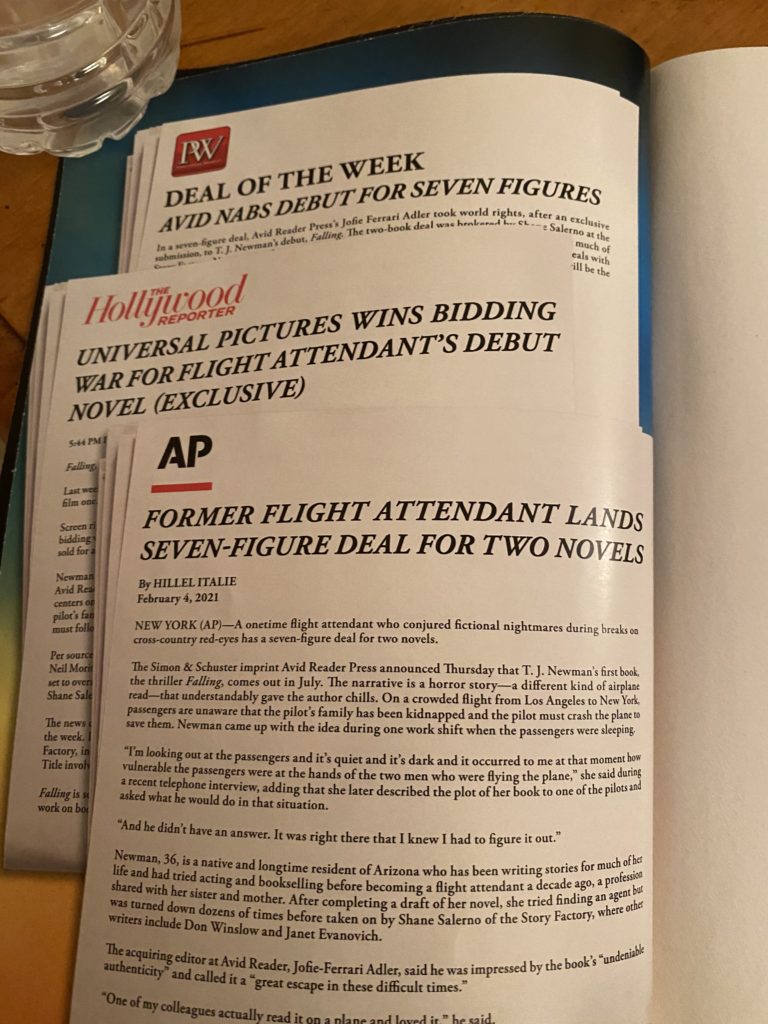

Forty-one agents rejected T.J. Newman’s debut thriller, Falling. The 42nd signed her up, sold it to the first publisher he contacted for a seven-figure, two-book deal. He also sold the movie rights to Universal Pictures. Falling was published just this week. It’s racing up the bestseller charts right now.

It’s the stuff of fairytales. The 21st Century equivalent of Lana Turner being discovered at the soda fountain of Schwab’s Drugstore on Sunset Boulevard. (And, if you never heard this story, or don’t know who Lana Turner was, sorry, you’ll have to google it!)

30 Drafts, Then Rejection by 41 Agents

But, if you’re an author and have gotten rejected time and again by agents (and you need an agent so that you can then be rejected by editors working for publishers LOL!) then you’re probably applauding T.J.Newman.

And, she deserves the applause. Talk about perseverance!

Can 41 Agents Be Wrong?

But like me you probably have a niggling thought at the back of your mind: How come 41 agents declined to represent her? Can 41 agents all be wrong? I think I have the answer.

For the last eight years, I’ve been dealing with agents and editors and story gurus. I’ve attended online seminars and in-person workshops and subscribed to author blogs and websites while working on my own thriller, Fool Her Once.

So, I’ve come to know a little about the mindset of those gatekeepers in the publishing business. And, now that I’ve read Falling, I can see what might have upset those 41 agents.

Thrilling Personal Story

But let me just back up a little here for those who haven’t heard about this amazing success story.

But let me just back up a little here for those who haven’t heard about this amazing success story.

T.J. Newman is a former flight attendant. Her personal narrative arc is almost as thrilling as her novel. She has told her story in newspaper and magazine interviews; on the radio, on major network television interviews.

She tells how she got the idea for a thriller about a pilot who is told to choose between crashing his plane or getting his wife, son and new baby killed by terrorists. She describes how the first pilot she tested the premise on, paled and turned away horror-struck.

She recounts how she persevered with 30 drafts before sending it off to agents; How 41 agents declined to represent her. How the 42nd, Shane Salerno, a Hollywood-screenwriter-turned-agent, signed her up and worked with her to polish her manuscript.

Unbeatable Premise

Well, Shane Salerno, screenwriter of action movies like Armageddon and Shaft , definitely knows a good movie when he hears about one. And the premise for this one is unbeatable.

You can just picture it now. There’s the drama in the air with the pilot, Bill Hoffman, being instructed to crash the plane; being sent a video of his wife and son wearing vests of explosives; being told there is an accomplice on board to make sure he carries out the deed.

Then there’s the drama on the ground with Bill’s wife, Carrie and their children who have been taken hostage by one of the antagonists. Their captor has to stay one step ahead of the FBI who have been alerted by the FBI agent, nephew of Jo, the plucky flight attendant.

So, Why 41 Rejections?

But wait, you say to yourself. With a premise as unbeatable as this one, how could 41 agents not have seen this thriller’s potential?

Well, you might say, if you’ve been rejected by an agent yourself, just goes to show, agents don’t know everything.

But still, you think, 41 of them? No, there’s something wrong with this picture. Forty-one agents can’t all be mistaken.

What’s Wrong With This Picture?

With this thought at the back of my mind, I started reading. I wasn’t sure at what point any of the 41 had rejected the manuscript.

Was it at the point where a writer sends a query with a short summary paragraph, a synopsis and maybe three chapters in the hopes of getting a full manuscript request. Or did T.J. get some full manuscript requests which were then rejected after an agent read the whole novel?

In T.J. Newman’s case I have a feeling that most of the rejections followed her initial query — especially if she included the first three chapters. This despite the opening lines of her Chapter One as follows:

When the shoe dropped into her lap, the foot was still in it.

She flung it into the air with a shriek. The bloodied mass hung in weightless suspension before being sucked out of the massive hole in the side of the aircraft.

Gotta keep reading. But wait!

Here Come The No-Nos — And, A Spoiler Alert

(In hazarding a guess as to what probably turned off 41 agents, I’m going to address specific plot points which you might not want to know about before reading the thriller!)

So, this is what I’ve learned from agents and editors over the past eight years: The first immutable, non-negotiable rule about openings is : Never, Ever Start Your Novel With A Dream. Never start your novel with your protagonist waking up.

And guess what? That thrilling opening of T.J.Newman’s is exactly that: A dream, or rather a nightmare that Bill the pilot is experiencing just seconds before being woken by his wife Carrie.

This is not just a no-no. It is a NO! NO! NO!

That’s because most agents and editors who deal with genre fiction will tell you that you’ve lured a reader in with a huge, dramatic life-and-death scene that turns out not to have happened. It’s simply a cheat; a bait-and-switch which is likely to turn off most readers at the outset. Why risk it?

Second No-No

According to most agents and editors, it is now considered a cliche, and therefore another no-no, to describe a protagonist by having him/her look in a mirror and describe what he/she sees there.

And guess what? Bill Hoffman, the pilot protagonist of Falling does exactly that. Okay, not exactly, but he looks at his reflection in a window at the airport to see that “a betraying gray salted his temples. His eyes a vibrant, deep blue.”

Say what?

A reflection in a window is not really going to give you the color of anything. Anyway, these paragraphs are hardly likely to endear the protagonist to the reader. On the contrary, Bill appears at this point to be something of a narcissist.

Worse, his thoughts on his good looks lead to the third No-No in publishing: the use of flashbacks that are not relevant to the plot.

Flashbacks

As any author knows, flashbacks/backstory are a contentious issue in thrillers because usually they slow down the action. Story guru, Robert McKee has a simple rule about flashbacks: The author should provide them only to satisfy a reader’s curiosity at the point where the reader needs to know what he/she wants to know.

That’s not exactly how the flashbacks in Falling work. Within the first two chapters of Falling, there are three flashbacks, and we know they are flashbacks because they are italicized. None of them are answering any pressing questions for the reader.

The first bounces off Bill’s reflection about his blue eyes, and he remembers that’s what his wife Carrie said she liked best about him. The second flashback takes him back to his first day of flight school. Why? Nothing happens here.

And the third flashback is a conversation with Jo, the heroine flight attendant about why she wears Shalimar perfume. Not a plot point anywhere in the book!

All of these happen within the first two chapters. Not to mention that the first sentence of Chapter Two has a noticeable typo in using the lower case for Bill’s name.

Antagonists?

I’m also puzzled as to who were the original antagonists in T.J.Newman’s early drafts. In Falling, they are very quickly revealed to be Kurdish. Their motive for crashing the plane is to bring attention to what they see as betrayal by their ally, the United States.

In real life, America’s abandonment of the Kurds, our allies in the war against ISIS, did not happen till November 2019, — after T.J. signed with Shane Salerno.

So, who were the antagonists of her earlier drafts? And, is it possible that they were undeveloped, one-dimensional villains without a “sympathetic” cause giving agents another reason to reject the story.

41 Agents Right Or Wrong?

There are a couple of other minor problems with plot points, but I agree with Tina Jordan’s review in the New York Times. Jordan writes: “Newman’s premise is terrific — so terrific in fact that it will divert you from thinking too much about the plot’s basic problems.”

Those problems along with the no-nos that agents were probably not willing to overlook cost 41 0f them a seven figure sale and the sale of movie rights.

Maybe there’s a lesson to be learned here for agents set in their ways, and bogged down in their rules and conventions. I know what that sort of intransigence can mean to an author — and so I applaud T.J. Newman 100 per cent.

As Robert McKee says, there really are no rules in writing. BUT, if you’re just starting out, you should know what the generally accepted “wisdom” about genre fiction is.

As Robert McKee says, there really are no rules in writing. BUT, if you’re just starting out, you should know what the generally accepted “wisdom” about genre fiction is.

And you should know that if you rebel against it you will need the fortitude and perseverance of a T.J. Newman to query — and get rejected by — many agents before finding the one who sees your potential.

Good Luck!