– Eleven Days before the Twin Towers Fell

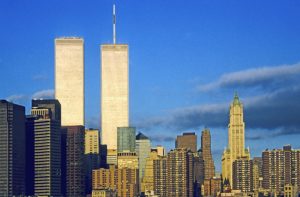

They were there from the moment I stepped off the plane from London in October 1978. For so long as I lived and worked in New York City, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre were the most identifiable, visible points on the skyline: Larger than life. In your face. Like the city itself.

They were there from the moment I stepped off the plane from London in October 1978. For so long as I lived and worked in New York City, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre were the most identifiable, visible points on the skyline: Larger than life. In your face. Like the city itself.

And, for sure, they were standing tall, glinting in the sun, the last time I saw them — 15 years ago, on August 31, 2001, the day I became an American citizen.

But I can’t say I really looked at the skyline that morning. It was not a morning like other mornings when I drove into the city. I didn’t stare or marvel, or silently feel the thrill the way I usually do when the skyline of the greatest city in the world suddenly slides into view.

I had other things on my mind that morning. I was a little nervous. Suppose INS agents had discovered something they didn’t like about me? Suppose they told me I couldn’t become a citizen today after all? Was I doing the right thing anyway?

For fifty years I had been a citizen of the United Kingdom, the country of my birth, so maybe it was natural I should feel like a bride on her way to church with last minute jitters. But, it wasn’t like I hadn’t had plenty of time to think this through. This day, after all, was the culmination of a love affair which had lasted for decades.

If I’m really pressed, you can sometimes get me to admit that a really bad 1963 movie, Beach Party, had something to do with it. But hey, I was an impressionable pre-teen when Annette Funicello and Frankie Avalon cavorted as students on spring break in sunny California. I wanted in.

Green Card

In my junior year of high school, I decided I was going to college in the USA. Because I wanted to impress on my father that I wasn’t just going for stuff like spring break, I sent for application forms to Vassar, Sarah Lawrence and Bryn Mawr (co-ed schools back then.) I realized quickly enough, however, that even if I got the grades, even if I got a scholarship, I’d never fit in at those Ivy League schools. Along with the application papers, one of the colleges sent a suggested list of outfits to bring. Topping the list was “a selection of formal evening wear.”

In my junior year of high school, I decided I was going to college in the USA. Because I wanted to impress on my father that I wasn’t just going for stuff like spring break, I sent for application forms to Vassar, Sarah Lawrence and Bryn Mawr (co-ed schools back then.) I realized quickly enough, however, that even if I got the grades, even if I got a scholarship, I’d never fit in at those Ivy League schools. Along with the application papers, one of the colleges sent a suggested list of outfits to bring. Topping the list was “a selection of formal evening wear.”

I shelved the dream. Frankie would have to wait. It would be another ten years before work as a freelance journalist allowed me to move freely between London and New York, and then another few years before I got my precious green card. It would take almost another twenty years to become a U.S. citizen even though INS regulations permitted me to apply for citizenship five years after getting my green card. Not because I didn’t try, or because I didn’t want to. But other things kept getting in the way.

The American Dream

I didn’t need to be an American citizen to pursue the American dream. I had a green card. I was allowed to work, and I did. For a while that’s all I did: I had two jobs . One at a tabloid magazine where I worked from 8a.m. to 3p.m, and the other in local TV news where I worked from 4p.m. to eleven at night. I couldn’t believe my luck.

This was the America I’d read about: If you worked hard, the rewards were plenty. Each year the rewards got a little better: a small studio on Madison Avenue (below 42nd); summer weekends on Martha’s Vineyard; a company car, an expense account, expenses-paid trips to Hollywood, Hawaii, Vegas, Monte Carlo, Paris.

Then came marriage, and motherhood. An American-born husband. An American-born son. Now, I had it all. I was living the American dream.

I did apply for citizenship as soon as I was eligible but there were stumbling blocks. Early application forms demanded a list not only of trips made outside of the US but the numbers of those flights. Who keeps a note of flight numbers? Then, came the fingerprint fiasco when it was discovered that the Clinton administration allowed thousands to slide past FBI background checks in the Citizenship USA rush to legitimize potential voters. It was followed swiftly by a crackdown on new applications. The first fingerprint form sent to me by the INS was rejected because the INS informed me it had sent me an outdated form. I called and asked for the updated form. The agency sent me the exact same form which had been rejected as invalid the first time.

I did apply for citizenship as soon as I was eligible but there were stumbling blocks. Early application forms demanded a list not only of trips made outside of the US but the numbers of those flights. Who keeps a note of flight numbers? Then, came the fingerprint fiasco when it was discovered that the Clinton administration allowed thousands to slide past FBI background checks in the Citizenship USA rush to legitimize potential voters. It was followed swiftly by a crackdown on new applications. The first fingerprint form sent to me by the INS was rejected because the INS informed me it had sent me an outdated form. I called and asked for the updated form. The agency sent me the exact same form which had been rejected as invalid the first time.

I took it personally. America didn’t want me.

Tax Break

It was our accountant who, subsequently, pointed out that resident aliens (green cardholders) like myself were foreign nationals, and so could not benefit from tax breaks that American spouses enjoy. In other words, if I did not become a US citizen I would not be able to inherit our marital property tax-free if my American-born husband died before me. It seemed like a less than noble reason to apply for citizenship, but as my husband pointed out it wasn’t the real reason, but merely the spur to try the application process again.

As it turned out, this time around was a good time to try again. The INS had seemingly gotten its act together. It promised that applications would no longer take several years to process. Indeed, barely a year after filing my renewed application, I was notified of a date for an interview and for my government and history test. Less than two weeks later, an invitation to my naturalization ceremony arrived in the mail. The whole process from filing the application to my swearing-in date was just thirteen months.

Twinge of regret

I was incredulous, but I was ready. I had read and re-read the oath of allegiance for naturalized citizens many times , scouring the fine print the way I always did with any contract even before I went to law school. Exactly what commitment was I making ? What would be expected of me as a citizen?

I’d be lying if I denied feeling a twinge of regret for renouncing allegiance to the country of my birth. England had been very good to me and my parents. England had given my parents a chance to rebuild their lives when they arrived with nothing in 1945 from war-torn Europe . England gave me a first-class – and free—education from kindergarten where I arrived not speaking a word of English through university which I graduated with a BA Honors degree in political science. England with its new National Health Service and its free orange juice, free milk and free cod-liver oil gave me the best of all foundations for a healthy life.

On the other hand, I had no problem with declaring on oath that I would “support and defend the Constitution.” Helping my seventh-grade son study for his social studies finals, just before my INS test, gave me a deeper appreciation for the Founding Fathers and their motivations, and for the 200+ years- old document they fashioned so carefully.

On the other hand, I had no problem with declaring on oath that I would “support and defend the Constitution.” Helping my seventh-grade son study for his social studies finals, just before my INS test, gave me a deeper appreciation for the Founding Fathers and their motivations, and for the 200+ years- old document they fashioned so carefully.

Bearing arms?

Nor did I have a problem declaring on oath that I would “bear arms on behalf of the United States when required.” I am not a dove. I don’t come from a family of doves. Both my parents fought in World War II. My father was a captain assigned to the British Army in the engineering corps and took part in the D-Day invasions. He then went on with his regiment to liberate the concentration camp where my mother, a Polish resistance fighter was imprisoned after the failure of the Warsaw Rising.

But back on August 31, 2001, when I became an American, eleven days before the unthinkable happened, the idea that America might get involved in a war where a 50-year old civilian wife and mother would have to bear arms was outright laughable. And, the possibility seemed remote that I would be asked to make good on the promise to “perform non-combatant service in the Armed Forces… or perform work of national importance under civilian direction.”

Back then on August 31, when I became an American, eleven days before terrorists declared war on the most powerful country on earth, I believed that because the Soviet Union had fallen, there would be no more world wars.

Back then, eleven days before thousands were massacred on American soil, I believed in the American intelligence agencies of film and fiction. I believed that America had spy satellites so sophisticated they could pick up the conversations of terrorists plotting thousands of miles from America’s shores.

Back then, eleven days before America was paralyzed by fear and grief, my Philadelphia -born husband told me I was very lucky because there were millions of people in the world who would give anything to be in my shoes.

New Citizen

After the swearing-in, after I’d raised my right hand and taken the oath of allegiance , the judge who was the granddaughter of a Russian immigrant who’d toiled in the sweatshops of the city addressed me and the other two hundred and thirty-seven new citizens. She told us to pursue our dreams, and to become involved in our communities, and to speak up for what we believed in.

After the swearing-in, after I’d raised my right hand and taken the oath of allegiance , the judge who was the granddaughter of a Russian immigrant who’d toiled in the sweatshops of the city addressed me and the other two hundred and thirty-seven new citizens. She told us to pursue our dreams, and to become involved in our communities, and to speak up for what we believed in.

And, then it was over, and I stood outside the courthouse and watched the other new citizens walk out with their families and friends. I joked with my husband that taking the oath of allegiance is a little like losing one’s virginity: No-one can tell by simply looking at your face that you’ve just become an American citizen.

It was okay to joke and laugh that day. It would be another eleven days before America stopped laughing. It would be another eleven days before the truth of the judge’s parting words came hammering back at me. “America is not a perfect country. But it is a great land.”

It would be another eleven days before I knew for sure that I had no problem at all with any of the promises I’d made.

But, back then it was August 31st. It was the Friday before the Labor Day weekend. I was anxious to get back home, to beat the traffic on the LIE to the East End of Long Island. I wanted to be on the beach.

I left the city in a hurry, speeding away on the BQE. I left without any backward glances across the river; without any glance at all at the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre.

I had no idea, not an inkling, not a single clue that I would never, ever see them on the skyline of the city again.

Photo credits (top to bottom) bigstockphoto.com w/ jorghackemann; MazelTov; Pamela Au; MarcoPolo

Excellent post, Joanna. Congratulations! Thank you for sharing.

Nick

Thanks Nick. Happy to share. It was such a momentous day.