Even if you’re not a professional writer, you may secretly — or not so secretly — harbor the ambition of writing a novel or a memoir. Whether it’s a rollicking good tale that you’ve created in your imagination, or it’s your own exciting/tragic/hilarious life story, you feel you have a tale to tell. And, if you actually sit down to write the book, you will quite likely reach a point when you decide to write your story as a screenplay.

Even if you’re not a professional writer, you may secretly — or not so secretly — harbor the ambition of writing a novel or a memoir. Whether it’s a rollicking good tale that you’ve created in your imagination, or it’s your own exciting/tragic/hilarious life story, you feel you have a tale to tell. And, if you actually sit down to write the book, you will quite likely reach a point when you decide to write your story as a screenplay.

I know I’ve done it many times. I love writing dialogue, but find that writing scene settings and physical descriptions is more of a chore for the most part. I’ve even taken the famous three-day STORY seminar with screenwriting guru Robert Mckee ( which I wrote about here and here) because I figured screenplays were the way to go; just so much easier to write, I’d tell myself.

Wide Margins

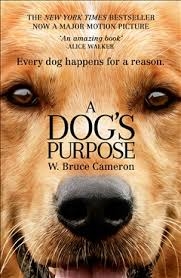

Bruce Cameron, the hugely successful, New York Times bestselling author of A Dog’s Purpose which sold 10 million copies worldwide, and was made into a movie seems to agree. He told an audience at the Palm Beach Book Festival last week that, of course, it’s easier to write a screenplay than a novel: “The margins are wider, and screenplays are short,” he said.

Bruce Cameron, the hugely successful, New York Times bestselling author of A Dog’s Purpose which sold 10 million copies worldwide, and was made into a movie seems to agree. He told an audience at the Palm Beach Book Festival last week that, of course, it’s easier to write a screenplay than a novel: “The margins are wider, and screenplays are short,” he said.

Cameron writes humor, and speaks with a great deal of it. He could be a stand-up comedian, and so, at the Book Festival he spoke in jest. Partly. It’s true that screenplays are shorter. A standard screenplay runs 100-120 pages compared to several hundred pages of a novel. And, yes, the screenplay format has wider margins. And, true, you can probably write one much faster than completing the first draft of a novel. But that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s easier.

Not Easier — Nor Harder

Andrew Ray, writer, director and guest speaker at this week’s Palm Beach Writers Group lunch told his audience: “It’s not a question of easier or harder. Writing a screenplay requires a different approach.”

For a start, he said: “In a novel, I can write about a character’s inner thoughts. But, in a screenplay I have to ask myself, what is the audience going to see? I have to show what the character is thinking or feeling.”

As a screenwriter you can do that by either describing the facial expression or through dialog. Consider, a scene where a middle-aged couple, about to be married, are sitting at a bar discussing where to go for their honeymoon. The bride-to-be, Laura, suggests San Francisco.

Novel vs. Screenplay

In a novel this might play out from the point of view of the husband-to-be, Tom as follows:

“He couldn’t believe his ears. Of all the cites in all of the world, she had to pick that one? Had she really forgotten that’s where he and Jessica had spent their four day honeymoon? Was Laura testing him?” He didn’t know what to say. No sooner had Laura named the city, then the images of Jessica had leaped unbidden into his head; Jessica sprawled naked across the huge king-size bed in the penthouse suite of the Mark Hopkins, the best hotel in the city.

He wanted to get out of the bar. It was one of those cool, hipster places where they asked you what brand of vodka you wanted in a cocktail — as if it really mattered. He downed his bourbon, and put his glass down on the counter firmly and with finality. He signalled for the check, reaching for his wallet. He and Jess, had spent the entire four days in that king-size bed, and he’d had no idea back then how soon the idyll would end; that within a week of returning home, it would all be over. And, Laura damn well knew the whole story.”

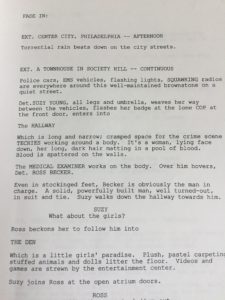

In a screenplay, you could write it as :

INT: Busy bar of a crowded city restaurant — Night. Laura and Tom sit at the bar, engaged in conversation.

LAURA

So, I was thinking, maybe San Francisco. They’ve got some really good deals for flights and hotels right now.

TOM

Tom downs the rest of his bourbon, bangs the glass down on the bar and signals the bartender for a check.

OR:

TOM

(snorts derisively into his glass of bourbon)

You’re kidding me, right? And, don’t tell me? The Mark Hopkins has the best deal of all?

Same Structure

The screenplay is definitely shorter on words, and direction, but both versions convey the idea that Tom is angry at Laura’s suggestion. In the novel, the reader knows that the suggestion is not an innocent mistake on Laura’s part; in the screenplay, it’s hinted. Note that in neither version does the reader or viewer know at this point why Tom’s first marriage ended.

The screenplay is definitely shorter on words, and direction, but both versions convey the idea that Tom is angry at Laura’s suggestion. In the novel, the reader knows that the suggestion is not an innocent mistake on Laura’s part; in the screenplay, it’s hinted. Note that in neither version does the reader or viewer know at this point why Tom’s first marriage ended.

However, both the novelist and screenwriter must know. When Laura mentions San Francisco, why does Tom react angrily at the memory of Jessica? Because Jessica left him for another man? If, on the other hand, the idyll with Jessica ended because she died or was killed, his reaction would surely be different. Instead of banging his glass on the bar, he’d maybe turn away, shrug, blink, swallow painfully, and perhaps order another drink without answering Laura. Hence, the screenwriter, just like the novelist, must know the protagonists’ motivations and back story. He/she must know, like the novelist knows, what the protagonist wants, and who wants to stop him or her, and how the protagonist is going to overcome the obstacles in his/her way. In other words, story structure –and its demands– is the same whether it’s a screenplay or a novel.

Collaborative Process

However, a screenplay is simpler when it comes to descriptions of settings and physical appearances. In a novel, a reader expects some scene setting and descriptions of the physical appearance of the main protagonists. In my novel excerpt above, I make the bar a cool, hipster city bar. In a screenplay, however, you can pretty much leave the details up to others like the director, or the set designer. As James Bonnett states in the Writers Store, ” the filmwright and the novelist are equivalent and have similar creative experiences, except that the novelist is a one man or woman band doing everything themselves, while the filmwright delegates many responsibilities to others.”

For example, in Paula Hawkins’s enormously successful psychological thriller, The Girl On The Train, the novel was set in England, and the female protagonist took a commuter train from the suburbs into the city of London. Hawkins described the ride and the homes alongside the rail tracks in some detail.

When Hollywood came calling, the action, for whatever reason, was moved to the Metro-North commuter line along the Hudson into New York City. Had Hawkins started with a screenplay she could have simply written:

INT. Commuter train on busy but picturesque line into a major city anywhere in English-speaking world.

No Details

By the same token, protagonists’ physical descriptions are important in novels. Not so much in screenplays. I may describe my female protagonist as short, with jet-black hair and someone who is constantly fighting a muffin top which materializes when she wears her favorite skinny jeans. However, it maybe that Reese Witherspoon reads the screenplay and wants to produce the movie– and play the lead female role. If the muffin top isn’t crucial to the plot, then physical description is simply not helpful in a screenplay.

Also, as Andrew Ray told the Palm Beach Writers Group, most good screenplays don’t have directions for the director. “The more directing notes you put in a screenplay, the harder it is to read it.” In other words, the screenwriter can write: “Tom and Laura engage in a physical altercation at the bar.”

A screenwriter does not have to write: “Tom grips Laura’s left arm with his right hand. She winces, smacks him away with her right hand, kicks him with her left foot under the counter and pushes him with both hands off his stool.” The director will have his own vision for the action after he reads the screenplay.

Too Many Cooks

On the other hand, “too many cooks [can] spoil the broth” as goes the old British saying. With so many voices having a say in its production, a movie may often stray from a writer’s original vision — especially if the screenplay is an adaptation of a book. Bruce Cameron, at the Book Festival, described what went into the movie adaptation of A Dog’s Purpose. “There were twelve separate writing teams brought in to work on A Dog’s Purpose. They hired all these people in Hollywood.” Cameron described how each team took the original concept and added to it, or rewrote till the idea became unrecognizable.

“So, then, ” he added, “they hired more people — to make the movie “more like the book.””

Good post, Joanna.

I wrote a screenplay last year and found it a much easier process as well. I too love to write dialogue.

Another great screenwriting resource is Blake Snyder’s “Save the Cat.” I developed my script using his beat-sheet process. It’s interesting to watch movies now, having read his book. You begin to see the patterns that exist in nearly every film.

Hi Doug, I remember your guest post here on this website about writing the screenplay. In fact, there is a link in this blog to your guest post. Maybe, I didn’t make it clear enough, but it’s in the section sub-headed, Wide Margins.

You did a great job explaining the differences between both processes! Thank you once again for doing the wrap-up of the PBWG speakers.

Thanks, Cathy. I always enjoy the PBWG lunches and speakers. Will miss them during the summer hiatus.

Another winner Joanna! Did you read Girl on a Train? I couldn’t get into that one.

Thank you, Eldon. I did read GOTT, and gave it a 4-star review on Goodreads a while back. One criticism I had, and maybe it’s the reason you couldn’t quite get into the book was that the three main female characters all sounded the same so it was difficult to tell whose POV it was.

I don’t think it was the POVs in my case – I didn’t get far enough in to notice. Just must’ve been the writing style that didn’t resonate with me. I’m in the minority with that one for sure – a huge hit for Hawkins!